When I was still working as a teacher, one of my students told me a story about a person they knew in the Tohoku region, who narrowly evaded death on March 11, 2011, the day the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami hit. This person was up on a roof, behind another tall building where more people had gathered, thinking they would be safe on higher ground. The tsunami wave struck the tall building, breaking against it in such a way that it shielded the lower roof where this person was standing. They survived; the other people were not so lucky.

That’s just one story. The Tohoku disaster resulted in almost 20,000 deaths, leaving the region devastated for years to come. You can feel the weight of that number even more when you’re standing in the empty Japan National Stadium on the anniversary of 3/11, as I did this week. The new National Stadium was built for the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics, which event organizers billed as the “Recovery and Reconstruction Games.” However, even after the Olympics were postponed for the first time in history — so that they landed in 2021, a decade after the disaster — not everyone had recovered.

Recovering from the “Recovery Olympics”

In the leadup to the Olympics, I remember talking to people and getting the sense that they felt the new National Stadium was mottainai, which is to say, a waste. Specifically, a waste of taxpayer money, which might have been better spent on the recovery effort in Tohoku.

Construction costs for the stadium amounted to over a billion dollars (157 billion yen), according to Nikkei Asia. Meanwhile, the final overall cost for hosting the Olympics exceeded $13 billion (¥1.4 trillion). As The Associated Press notes, over half of that came from taxes, with at least one study indicating that “in most cases the Olympics are a money-losing proposition for host cities.” (What makes this all the more topical is that today is Tax Day in Japan.)

At the end of last year, The Asahi Shimbun also reported that the public will continue to foot part of the stadium’s maintenance bill, meaning it’s still financially recovering from the Recovery Olympics, to the tune of $7.46 million (¥1 billion) per year. The hope is that subsidizing costs like this will give one or more private companies incentive to take control of the stadium’s operations and pay the rest of the annual maintenance bill. In the meantime, the stadium is just kind of sitting there without a whole lot going on inside of it.

By March 2021, the government had spent about $359 billion (¥13.46 trillion) on recovery in Tohoku (via Nippon.com). We’re dealing with astronomical figures here, but when you weigh that figure against the Olympic costs, it put things in perspective. The government was already spending a lot to help the people of Tohoku; the only question is whether the notion of the Recovery Olympics was misguided, especially since the country and the world hadn’t recovered from the pandemic yet, either.

The White Elephant in the Room

Next week, Japan’s national football/soccer team, the Samurai Blue, will play its first game since the World Cup at the new National Stadium. The place does serve as a venue for some events, though it doesn’t seem to have many scheduled. Add to this the fact that the general public was barred from the opening and closing ceremonies for the Olympics (again, because of the pandemic), and it starts to feel like the stadium hasn’t had much discernible use yet for the citizens paying for it.

Only a fraction of the seats were filled during the drone-assisted opening ceremony, mostly by the media and dignitaries like the Emperor. With the absence of spectators, The New York Times described the stadium as a “sea of empty seats”—a sight the 1988 anime film Akira once predicted.

The stadium’s original design, by the late Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid, called for a retractable roof and a site that would occupy more acreage, intruding upon the nearby Meiji Shrine Outer Garden. It would have cost over twice as much, and the design was deemed impractical, or perhaps just not Japanese enough.

Critics called it a white elephant, but the phenomenon of a leftover stadium — built expressly for the Olympics as a symbol of national pride for the host country — is hardly unique to Japan. As the Times notes, similar white elephants have been left behind in places like Montreal and the original Olympic city, Athens, Greece.

Ultimately, Hadid’s design was scrapped in favor of a scaled-down redesign by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. The stadium was completely fenced off and under tight security during the Olympics, but now it’s open for tours on select days. After everything Tokyo went through to arrive at the building of this venue and hosting of the Games, I was curious to see inside and see if it was worth it. That’s how I came to join one such tour last Saturday, March 11, at 3 p.m., just after the anniversary of the quake at 2:46 p.m.

Japan National Stadium Tour

The tours are conducted in Japanese, but they do have a single crinkled printout explaining everything in English, which you have to turn back in at the end. We entered through the Origami Hall, which takes its name from its ceiling, designed to look like origami folds. Inside the stadium, which has three tiers, the first area we saw was the 2nd-floor VIP seats, centered in the main grandstand.

From there, we were ushered into the VIP lounge, which has windows lined with shoji paper sliding screens. Through the windows, you can see the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium and NTT Docomo clock tower, though you’ll have a better open-air view from the Sky Forest (Sora no Mori), an outside walkway on the 5th floor that’s the only part of the stadium open to the public, as far as I could tell.

Leaving the lounge, we passed a folding screen by calligrapher Bisen Aoyagi before entering the 3rd-floor “VVIP” lounge, which emerges into a terrace overlooking the stadium. As its name suggests, this is where very, very important people like the Emperor spent time during the Olympics.

On the 4th floor, we walked along the spectator concourse, another outside walkway like the Sky Forest, where I could observe some of the parallel cedar latticework along the eaves. In Japanese, they call this style nokihizashi. The greenery planted above the eaves is meant to gel with the Meiji Shrine Outer Garden.

The final stop was the upper observation deck, from which we could survey the steel-and-wood roof and all 68,000 stadium seats. They’re colored in alternating earth tones and “meant to portray sunlight filtering through trees in a forest,” according to the information provided.

The New National Ghost Town

Across the street from the new National Stadium is the Japan Olympic Museum, which has a rings display outside. If you make a little sojourn to one of these places in autumn, you can pair it with fall color viewing along the famous ginkgo street in the Meiji Shrine Outer Garden. I did it with the old National Stadium one day in 2013, and I also walked through the area again in 2015 after the stadium was demolished but before any part of the new one had arisen. At that time, you could see straight through to the skyscrapers of Shinjuku from the ground.

Inside the old National Stadium in 2013.

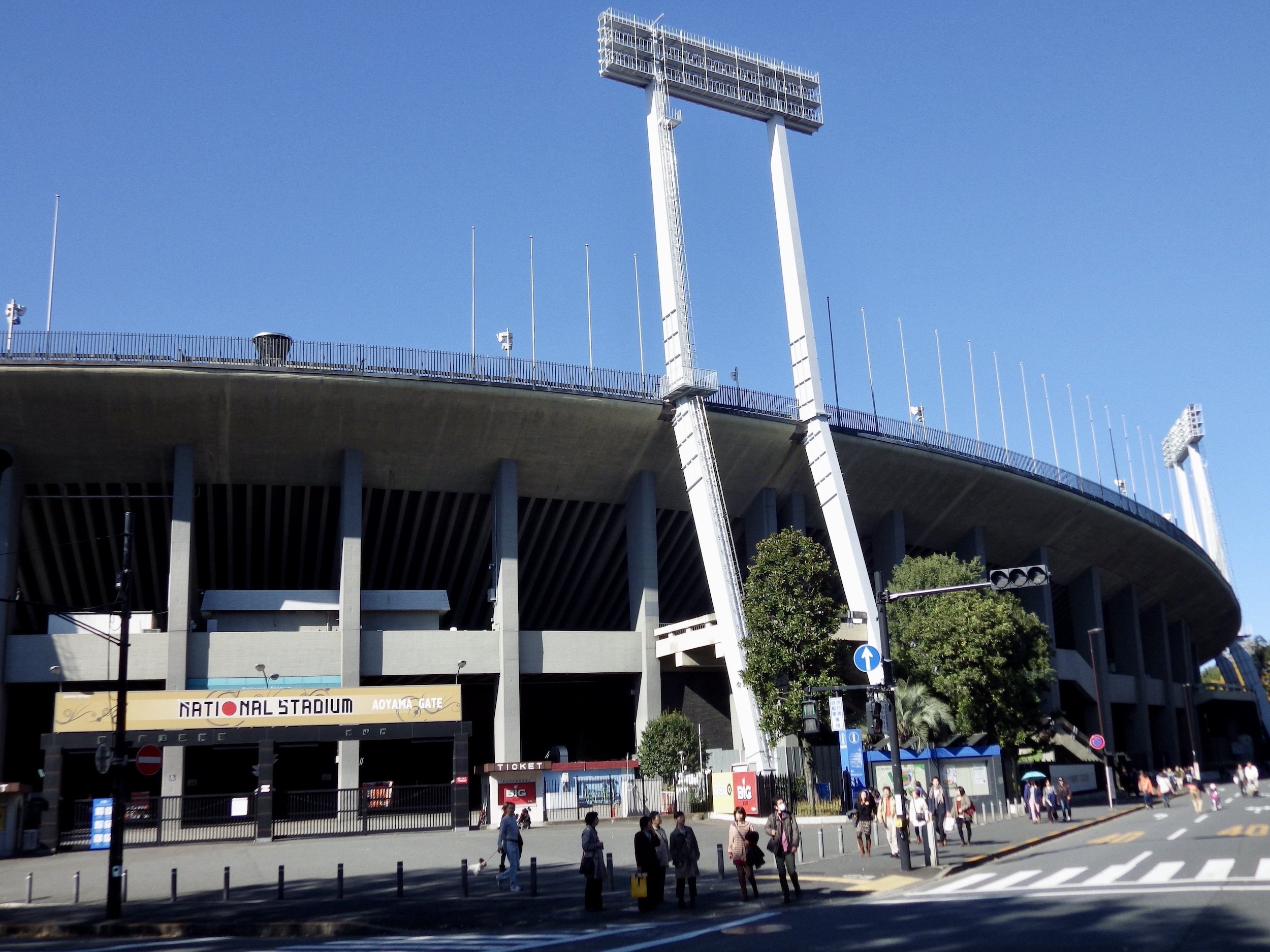

Outside the old National Stadium.

Construction site for the new stadium in 2015, with Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium and the skyscrapers of Shinjuku visible.

Over the years, from buildings like Shinjuku Park Tower and Shibuya Scramble Square, I saw more of the stadium pop up under construction cranes. Seeing it from the inside this week — built but empty, on the anniversary of 3/11 — it was haunting to think that a third of the seats could have been filled by people who lost their lives in the Tohoku disaster.

The stadium is impressive, as are the achievements of all the athletes who participated in the 2020/2021 Tokyo Summer Olympics. But this wasn’t Tokyo’s first Olympics, and ultimately, the question of whether it was worth it to build this stadium is one that’s too big for me to answer. As I looked out over its 68,000 unoccupied seats, I felt more like I was surveying the new National Ghost Town. That’s not so different an image from the one that forms when you hear about clocks that still sit frozen and schoolrooms and other places that still sit abandoned in Fukushima Prefecture, after the Tohoku disaster triggered the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl at the power plant there.

Time stopped for people that day, and the older I get, the more I realize how true it is that time waits for one. The years go on without you, and in the end, maybe every building and all human endeavors are just one long parade of white elephants through history.