“One day a fugitive appears in a village. He enjoys the calm, friendly atmosphere there, but also senses that something is not quite right.”

This is the simple but intriguing setup for the movie Gutland, provided by the official guide to the 30th Tokyo International Film Festival (hereafter referred to as TIFF-JP, in order to differentiate it from the Toronto International Film Festival, where Gutland made its world premiere in September).

Writer-director Govinda Van Maele, who hails from Luxembourg, first emerged on the film festival circuit ten years ago with a short film entitled Josh. It seems only fitting, then, that the winsome gut lord behind The Gaijin Ghost — coincidentally also named Josh — should take a quick stab at reviewing Gutland. The film screened in competition at TIFF-JP yesterday, and it marks a very assured debut feature for Van Maele.

'Gutland' - The Gaijin Ghost Review

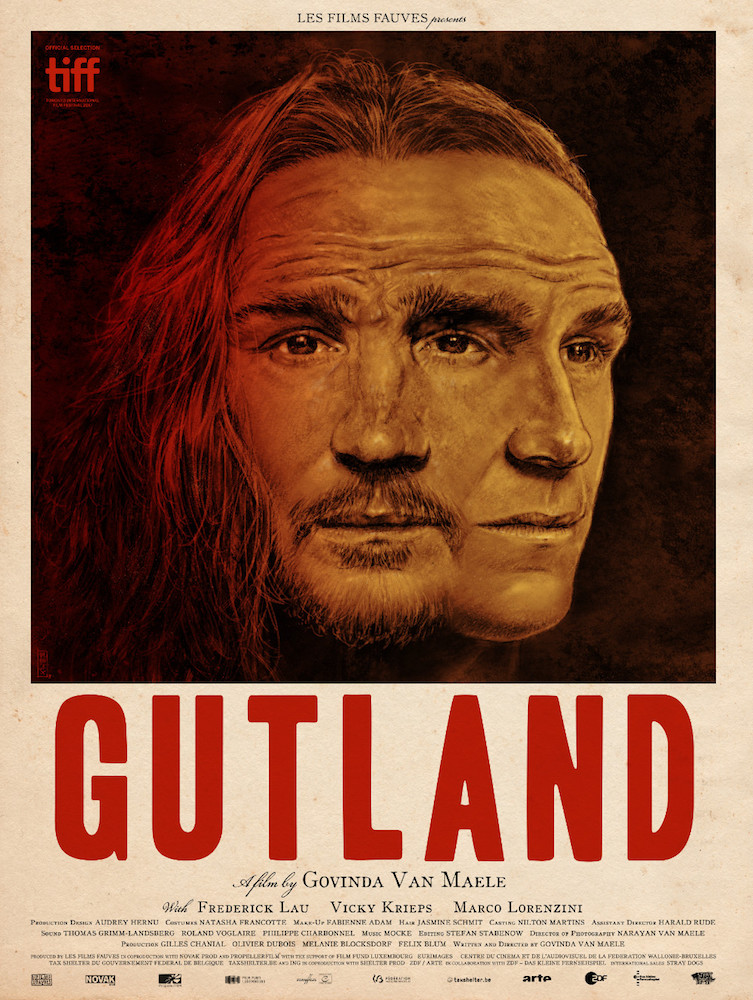

Frederick Lau in Gutland. (c) Les Films Fauves - Novak Prod - Bauer & Blum - ZDF/Arte - 2017

For those hesitant about watching a potentially slow-paced foreign film with English subtitles, rest assured, Gutland’s basic genre premise as a “surrealist rural noir” is enough to lure in the viewer and sustain interest throughout its 107-minute runtime. The film is engrossing from the first minute, when the fugitive Jens (Frederick Lau) wanders into town in search of seasonal work as a farmhand.

While American audiences might be unfamiliar with his face, Lau’s rugged physiognomy does hold the screen. With his long hair and Qui-Gon Jinn beard, he could almost pass for Liam Neeson’s long-lost brother.

In her role as Lucy, the local girl who seduces Jens, Vicky Krieps (upcoming: Phantom Thread) is also luminescent. Lucy’s got an edge to her, but her beatific smile charms Jens and he soon develops more complicated feelings for her as he heeds the siren’s call.

Production still of Vicky Krieps from the official Gutland website.

Settling into the mundane job of harvesting wheat and dealing with dairy cows, it’s not long before Jens discovers that Lucy’s agricultural community holds some dark secrets. “Chekhov’s knock-out dart” gives us ample warning that the bucolic Schandelsmillen, as the village is called, may seek to subdue someone before the film is over. By the time Jens gets lost in a wheat field with the sound of a combine harvester bearing down on him, the village has begun to feel like a prison from which there is no escape.

Gutland is an actual region of Luxembourg; the name means “Good Land.” Early on, Lucy talks about how she doesn’t have the guts to leave. Other than that line, and the sight of a literal potbelly here and there, the significance of the movie’s title appears to lie more in its irony. Van Maele gives the picture of communal and domestic bliss an undercurrent of carnality and horror. It’s an erotically charged “Good Land” where the bad bubbles up in a slurry pit behind the house.

This is a movie about what happens when the caveman and criminal in all of us goes clean-cut. “How deep did you bury it?” someone asks Jens, and they might as well be asking about his old identity. It’s mostly light touches of surrealism that show up in Gutland: a woman disappearing in shadows, photographs that seem to change appearance, a brass band performance that could be unsettling and/or redeeming, depending on how you look at it.

Govinda Van Maele Press Conference (Potential Spoilers)

This veers close to spoilers for the ending of Gutland, but at a short press conference following the film’s screening at TIFF-JP yesterday, Van Maele discussed the real-life inspiration for that brass band, saying:

“There are a lot of brass bands in Luxembourg, in every village, and they like to play Hollywood theme songs. When you walk around at night, you can hear songs from Lord of the Rings and Jaws in the air as they rehearse. I wanted to give my film a kind of kitsch Hollywood-sounding ending. It’s both a nightmare and a happy end at the same time.”

The interesting thing about Gutland is how it almost plays out as an unlikely redemption story, like a slice of folk horror where the religious cult saves someone and sacrifices their enemies instead. When the domesticated wild child lets another person dress him the same way as everyone else, though, it raises questions about the line between conformity and group harmony.

What part of themselves does a person have to give up to find a sense of belonging somewhere? Is there happiness to be found in assimilation?