Tomorrow, Oppenheimer hits theaters in the U.S., though it doesn’t have a release date yet in Japan, maybe for reasons of cultural sensitivity. Would Japanese audiences really want to watch an American movie about the father of the atomic bomb?

In this biopic of theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, director Christopher Nolan is confronting U.S. history head-on with a story set against the Manhattan Project’s research and development of nuclear weapons during World War II. Yet Oppenheimer isn’t the first time that a Nolan film with Cillian Murphy in it has brushed up against American history and the potential perils of technology, nuclear or otherwise.

Speaking of history and the uncertainty of movie releases, this has been an eventful week in Hollywood and in my own professional life. I will have more to say about that in the future, but at present, I’ve got bats on the brain. Join me now in a deep dive from the belfry of that Gothic cathedral into the shadowy, subtextual underground of a trilogy that includes two of my favorite movies. We’re here to talk about The Dark Knight trilogy, where bombs are a recurring plot device and Murphy’s Scarecrow is a recurring villain.

The Gotham Project

The connection between the “American Prometheus,” as the book that inspired Oppenheimer refers to him, and Batman Begins, The Dark Knight, and The Dark Knight Rises might run deeper than you think, if you have a mind to go spelunking (“Yeah, you know, cave diving?”) for it. Instead of a desert site called Trinity in New Mexico — where the first nuke was detonated 78 years ago this week, on July 16, 1945 — Christopher Nolan staked out a piece of the pop culture landscape with his Batman film trilogy as a testing ground for ideas related to technology, ticking time bombs, and warning signs of the decline and fall of the new Roman Empire, America.

The Applied Sciences division of Wayne Enterprises and its R&D department serve as a kind of superhero movie Manhattan Project. All they’re missing is a name switch, like in The Batman, where there’s a Gotham Square Garden (and the Caped Crusader calls his crimefighting mission “The Gotham Project” in his diaries). In The Dark Knight Rises, which used the actual island of Manhattan to double for Gotham City, Wayne Enterprises is even indirectly responsible for the threat of a four-megaton nuclear bomb when the core of a fusion reactor it has developed in the name of clean energy falls into the wrong hands.

The movie opens with the supervillain Bane (Tom Hardy), staging an elaborate airborne kidnapping of a nuclear physicist, Dr. Pavel (Alon Moni Aboutboul). This scene was plainly inspired by the opening of the James Bond film Licence to Kill, where Timothy Dalton’s Bond (in full wedding attire, no less) ties a tow cable around a plane’s tail, allowing the helicopter above it to upend the plane mid-air. But Dr. Pavel can also be read as a fictional successor to Oppenheimer, who Nolan called “the most important person who ever lived” at CinemaCon this year (per Variety). Intent on ushering in “the next era of Western civilization,” Bane later drags Pavel out onto the field in a packed football stadium and executes him after a boy sings the National Anthem there.

For Heath Ledger’s Joker in The Dark Knight, two bombs are always better than one. And as I wrote in a 15th-anniversary article for Inverse on Tuesday, it’s no coincidence that he’s a villain who uses weapons of mass destruction. The Dark Knight tapped into cultural anxieties about surveillance technology and the war on terror. The film’s politics may be debatable, but as mentioned in the article, it even found its way into the 44th U.S. president’s foreign policy discussions. According to The Atlantic, Barack Obama once told his advisers, “[ISIS] is the Joker. It has the capacity to set the whole region on fire.”

A Big White Lie

What separates the Joker from ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) is that he’s a domestic terrorist. That’s an important distinction to make, since, as Cillian Murphy’s villain, Dr. Jonathan Crane, notes in Batman Begins: “Patients suffering delusional episodes often focus their paranoia on an external tormentor.”

Batman seems to know that because The Dark Knight ends with him choosing to serve the public interest by letting Gotham’s law-abiding citizens scapegoat him — someone who operates outside the law — as an external evildoer. In doing so, he maintains a rather big white lie, the fantasy of the noble district attorney with vaguely Aryan features, Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart).

For the greater good, Batman shoulders the blame for Dent’s crimes himself, taking the literal fall for the bad guy from the burned-out building where one of Joker’s bombs killed their mutual love, Rachel Dawes (Maggie Gyllenhaal). This is followed by a God’s-eye view shot of Dent and Batman — “Gotham’s white knight” and the titular Dark Knight — lying side-by-side on the ground.

In the moment, Batman’s lie seems like a necessary evil to keep Gotham from losing hope, and to keep all the good Dent did as a crusading D.A. (before he broke bad as Two-Face) from being undone. It’s this supreme self-sacrifice that makes Batman the true hero, one of many in a long line of cinematic Christ figures (which includes Superman, E.T., and Andy Dufresne of The Shawshank Redemption, as I’ve noted elsewhere).

Though the Joker teases that they’re perhaps “destined to do this forever,” Batman doesn’t want to let this lip-licking devil win “the battle for Gotham’s soul.” He wants people to see the good in Dent. As he says, “Sometimes people deserve to have their faith rewarded.”

Dent, by contrast, can only see the bad in people at this point. He believes Jim Gordon (Gary Oldman) is the one who’s made a “deal with the devil” by working with the corrupt cops Dent investigated while he was making his name in Internal Affairs. When they first meet, Gordon, the world-weary realist, tells Dent that the only other alternative would be for him to work alone. “I don’t get political points for being an idealist,” he says. “I have to do the best I can with what I have.”

Justice vs. Revenge

Gordon’s resignation to accept the dirty cops around him goes back to what we saw of him in Batman Begins, where his own partner, Flask (Mark Boone Jr.) was as corrupt as they come. The movie showed how Gordon refused to rat on Flask or any of his fellow officers, rationalizing, “In a town this bent, who’s there to rat to, anyway?” There’s dignity in that stance insofar as it upholds Gordon’s personal code of integrity and keeps him from being a “squealer,” as the Joker would say. Yet Gordon’s failing in The Dark Knight is that he allows the corruption in his own unit to go unchecked, indirectly resulting in Rachel’s death and Dent’s disfigurement, since the two cops who handed them over to the Joker were under Gordon’s command.

In a moment of desperation at the end of The Dark Knight, Gordon confesses to Dent, “Harvey, you’re right. Rachel’s death was my fault.” He recognizes his role in the tragedy that’s unfolded, as does Batman, who says, “What happened to Rachel wasn’t chance. We decided to act.” But Dent can’t see that; he’s stuck on the idea that the world is cruel and unjust and has unfairly targeted him. The character arc of “Harvey Two-Face,” self-righteous hypocrite, is an inversion of Batman’s arc.

That arc, too, goes back to Batman Begins, where the young Bruce Wayne runs the risk of becoming a garden-variety vigilante, “just a man lost in the scramble for his own gratification,” as Ra’s al Ghul (Liam Neeson) puts it. Bruce even shows up to court with a gun and is ready to shoot Joe Chill (Richard Drake), the man who murdered his parents. Mob boss Carmine Falcone (Tom Wilkinson) beats him to the punch, showing Bruce how dangerously close he is to becoming the very thing he abhors: a criminal and killer. The Katie Holmes version of Rachel then schools him on the nature of justice and its inherent blindness, saying: “Justice is about harmony. Revenge is about you making yourself feel better.”

It’s a lesson that Eckhart’s Harvey Dent fails to learn, as he abandons justice for revenge and “blind, stupid, simple, doo-dah, clueless luck,” as his grandstanding forebear, Tommy Lee Jones, once called it.

Buried Secrets

In the end, both Harvey Dent and the Joker are proven wrong about humanity in The Dark Knight. The Joker does, as he says, bring Dent down to his level, but he doesn’t succeed in proving “that deep down everyone’s as ugly” as him. It’s by design that the boat full of condemned men — prisoners, the same criminals Dent put away — is the one that does the right thing and throws the Joker’s detonator out the window, refusing to blow up the other boat full of civilians in the third act.

This subverts the Joker’s plan, which resembles the one that Ra’s al Ghul implements in Batman Begins. Both plans involve pitting Gothamites against each other. Ra’s (one of early Christopher Nolan’s prescient gas mask wearers) does that by gassing them with a “misplaced” microwave emitter, yet another piece of Wayne Enterprises tech gone wrong. We’re told the microwave emitter was “designed for desert warfare,” much like the Tumbler with its desert camouflage color, but Ra’s goes on the offensive with it, just as Bane does with the reactor-turned-bomb.

“Tomorrow the world will watch in horror as its greatest city destroys itself,” Ra’s promises. The Joker believes the same thing will happen, telling Batman in the interrogation room, “When the chips are down, these ‘civilized’ people will eat each other.” They don’t do that in The Dark Knight, but in its sequel, they do eat the rich.

The Dark Knight Rises is a messier movie, but despite its flaws, it brought the trilogy full circle in more ways than one. Lest we forget, Batman Begins started with 8-year-old Bruce Wayne (Gus Lewis), doing what capitalists and graverobbers do best (according to the new Indiana Jones movie, anyway) and stealing. He swipes an arrowhead from young Rachel Dawes (Emma Lockhart), pointing out that she found it in his garden after she says, “Finders keepers.” Nevertheless, if you were to play semantics and really dig deep into the symbology onscreen, then technically, the Wayne family is living on land stolen from Native Americans, the Indigenous people who left that arrowhead there in the first place.

Beginning the trilogy with a scene where kids take turns stealing this relic from America’s past serves as a subtle reminder of the nation’s buried secrets. They’re really more like open secrets, another one being the great contradiction of the supposed “land of the free” founding itself as much on the Transatlantic slave trade as the notion of democracy.

Gotham, Rome, and America

In The Dark Knight Rises, the secrets emerge from the sewers with Gotham’s resident demagogue, Bane, and the League of Shadows. It’s worth reviewing their history: Ra’s al Ghul says the League “sacked Rome” and has spread plagues in other cities, destroying capitals “every time a civilization reaches the pinnacle of its decadence.” It’s maybe also worth reviewing some of the ways The Dark Knight and its sequel wound up overlapping with real-world events in the undoubtedly decadent (and of late, plague-afflicted) civilization where I grew up: America.

To quote The Godfather, by way of the first page of Batman: The Long Halloween: “I believe in America.” Or at least I, like Fox Mulder, want to believe in America. That’s where I was living the summer of The Dark Knight.

NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden (later the subject of a biopic starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt of The Dark Knight Rises) first considered leaking classified info around the same time in 2008 (per Vanity Fair). As chance would have it, when he finally fled the U.S., Snowden sought to avoid extradition in Hong Kong, much like Chin Han’s Gotham mob accountant, Lau.

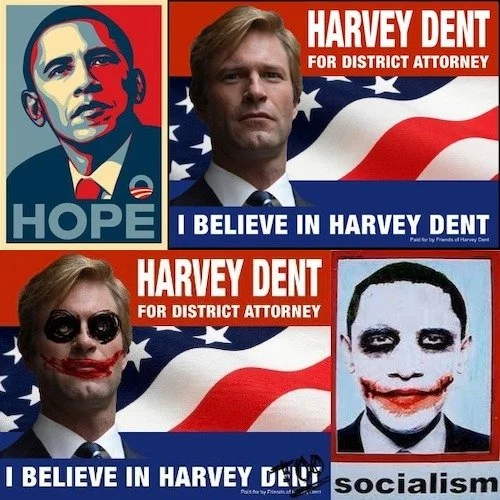

Barack Obama, meanwhile, went from inspiring “HOPE” with a notable campaign poster to having his face doctored to look like Heath Ledger’s Joker with the word “socialism” below it. Life imitated viral art, where fans had likewise seen Harvey Dent’s all-American poster defaced with panda bear eyes and a sloppy red grin.

One of the first widely reported instances of the Joker-ification of Obama came at a vice presidential rally for Joe Biden at Florida State University while I was a student there. Two FSU College Republicans were behind it. Now might be a good time to mention that I’m registered to vote as an independent.

I also visited Hong Kong—and departed on June 23, 2013, the same day Snowden left. So, this stuff has sort of followed me around. Years before he played the Joker, I happened to be in the live studio audience, too, when Heath Ledger appeared on The Daily Show in New York. Despite being inspired more by A Tale of Two Cities and the French Revolution, the production of The Dark Knight Rises crossed paths with the Occupy Wall Street movement there (and apparently considered filming the protests, though actor Matthew Modine told Indiewire that Christopher Nolan decided against it).

In The Dark Knight Rises, Bane shoots up a stock exchange, bankrupts Batman, and incites Park Avenue riots and kangaroo courts, judged by the master of fear, Scarecrow. In the same way that Nolan’s filming locations and Gotham’s cityscape changed from Chicago to New York (they both look nothing like the soundstage Gotham in Batman Begins), Bane thereby shifted The Dark Knight trilogy’s ever-evolving central fear. It went from being fear itself in Batman Begins, and terrorism/anarchy in The Dark Knight, to populism and economic inequality in The Dark Knight Rises.

Trump and Bane

Coincidentally, in The Dark Knight Rises, a building owned by the next U.S. president, Trump Tower, appears on camera as Wayne Enterprises. Maybe that’s why Donald Trump latched onto the film, reviewing it on YouTube and later echoing a Bane quote in his inauguration speech, as The Guardian notes. Cross-reference Trump’s line about power and “giving it back to you, the people,” with Bane’s line, “And we give it to you, the people.”

This wasn’t the first time Trump echoed a Batman villain, either. He also had that infamous line (via CNN), “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn't lose any voters.” That one had a whiff of Carmine Falcone to it, saying in a room of people he owns, “I wouldn't have a second's hesitation of blowing your head off in front of them. Now, that's power you can't buy.”

The Dark Knight Rises took flak for conflating Bane’s riot mob with Occupy Wall Street, but in hindsight, Trump’s rabble-rousing makes the civil unrest in Gotham look more like the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. In the context of a superhero movie, Christopher Nolan managed to deliver a prophetic 2012 warning against the cultural decline into insurrection, enabled by a populist leader and an angry mob.

In The Dark Knight, the Joker exploits a different mob mentality, the greed of organized crime, before burning their accountant atop a pile of money. Unlike Ra’s al Ghul and the League of Shadows, which first sought to exploit “economics” as a weapon against Gotham, the Joker has no use for money, which is part of what makes him unpredictable and scary. Civilians are fair game for him, too, not just the rich. After his successful twin bomb plot with Harvey Dent and Rachel Dawes, the third act circles back to bombs again and sees Joker maneuvering to have the evacuees aboard two ferries blow each other up out of the basest instinct for self-preservation. How will they do it? By voting.

Substitute political parties for ferries, and if it wasn’t already clear, Gotham functions on one level as a stand-in for the U.S., with the threat to it potentially coming as much from inside as outside if one votes the wrong way.

Islands and Bridges

The Dark Knight trilogy depicts Gotham as an island city, and in all three movies, the villain blows up every bridge off the island or forces the authorities to block them off. It’s a good visual metaphor for a country burning bridges while teetering on the brink of isolationism, like the U.S. under Donald Trump’s “America First” slogan, which had roots in a previous isolationist policy that the Ku Klux Klan once advocated.

Despite such dog whistles and his “bothsidesing” of a white supremacist car attack in Charlottesville, Virginia, not all of Trump’s voters were KKK members. If Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway) is any indication, not everyone present during the riots in The Dark Knight Rises was an all-out comic book villain, either. In Batman Begins, a recent economic depression (as opposed to the Great Recession of The Dark Knight’s time) is actually part of the backstory. Harvey Dent’s doomed D.A. predecessor, Carl Finch (Larry Holden), argues that “working people like Mr. [Joe] Chill,” who gunned down Bruce Wayne’s parents, were “hit hardest” and “motivated not by greed, but by desperation.”

Chill may not bolster the case very well, but Finch positions him as a symptom of a larger problem, the same one that makes the decoy Ra’s al Ghul (Ken Watanabe) think, “Gotham’s time has come, like Constantinople or Rome before it.” Part of the issue is that Carmine Falcone “keeps the bad people rich and the good people scared.” There’s been an erosion of values and a slide toward greater injustice. Witness Flask, one of many cops on Falcone’s payroll, pointing his gun at a Black citizen, threatening “excessive force” after the man accuses him of police harassment.

That’s a movie vision of the type of abuse of power that sparked the George Floyd protests in real life. What the police are meant to do is serve and protect, and the same could be said for the military. Incidentally, in Japan (a legit island country with an isolationist past), they call the military the Self-Defense Force.

The Argus-eyed sonar system in The Dark Knight could have started out as one of the abandoned “defense projects” in Applied Sciences at Wayne Enterprises. When Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman) sees what Batman’s done with it, he has an Oppenheimer moment where he realizes the gravity of what he’s unleashed. “Spying on 30 million people” has implications that go beyond big government to Big Tech. The danger of it carries forward into The Dark Knight Rises when the ground drops right out from under Batman’s “precious armory” in Applied Sciences, and Bane co-opts all his weapons.

Tragically, headlines offscreen showed what weapons in the wrong hands can do, too.

Aurora’s Dark Night

The Dark Knight Rises isn’t the first movie I saw in a theater in Japan, but it is one of the earliest, most vivid memories I have of that kind of filmgoing experience. Midnight movie showings aren’t as much of a thing here as they were in my college town in Florida, so when I went to see The Dark Knight Rises in 2012, it was at 12:30 on a Friday afternoon. The venue was a MOVIX theater in Dream Plaza, a shopping mall with a Ferris wheel in the port of Shimizu-ku, Shizuoka. Japanese-language posters and standees of Batman and Catwoman decorated the lobby.

The movie opened a week later here than the U.S., on July 27, 2012, so by then, it had already been overshadowed by news of the mass shooting that took place at a midnight premiere in Aurora, Colorado, 11 eleven years ago today. News of this shocking crime, carried out with real American guns of the kind Harvey Dent recommends buying in a fictional courtroom, hit close to home, just as Heath Ledger’s death had back in 2008. With twelve people dead and dozens more injured in one of the worst mass shootings in U.S. history, it made the movie seem trivial.

After that, it was hard to watch a masked supervillain, Bane, and his men fire off uzis and crack skulls in a crowded stock exchange without thinking of the gun massacre in Aurora. I kept picturing the inside of the AMC 20 multiplex in the Tallahassee Mall back home in Florida. I could see the red glow of the emergency exit sign, like some twisted dramatization of a line from Batman: The Killing Joke: “Madness is the emergency exit.”

At the time, President Obama “ordered that all American flags be flown at half mast” (via The Hollywood Reporter), while Christopher Nolan issued this statement:

"Speaking on behalf of the cast and crew of The Dark Knight Rises, I would like to express our profound sorrow at the senseless tragedy that has befallen the entire Aurora community. I would not presume to know anything about the victims of the shooting but that they were there last night to watch a movie. I believe movies are one of the great American art forms and the shared experience of watching a story unfold on screen is an important and joyful pastime.

"The movie theatre is my home, and the idea that someone would violate that innocent and hopeful place in such an unbearably savage way is devastating to me. Nothing any of us can say could ever adequately express our feelings for the innocent victims of this appalling crime, but our thoughts are with them and their families."

Occupations and Preoccupations

Watching from abroad on my laptop and phone as the Aurora tragedy and other disturbing events have unfolded in the U.S., I’ve sometimes felt like Bruce Wayne at the bottom of his prison hole in a foreign land, seeing Gotham City go to hell in a handbasket on TV. Substitute America for the theater, and I can relate very much to Christopher Nolan’s statement, “The idea that someone would violate that innocent and hopeful place in such an unbearably savage way is devastating.”

To my surprise, what I couldn’t relate to as much was the actual storytelling in The Dark Knight Rises. Despite the sudden baggage around the film, it never occurred to me, as I sat down in the theater in 2012, that there was even a remote possibility I might not like Nolan’s trilogy ender. However, even as a Nolanite (back when saying, “In Nolan we trust,” was still in fashion in online comments), I had some issues with the film, too many to enumerate in the context of an already sprawling post like this. If I can paraphrase Jim Gordon, though, some of those issues boil down to the film’s clunky dialogue and the question, “But what about [exposition]?”

A living embodiment of that is the Special Forces operative, Captain Jones (Daniel Sunjata), who shows up late in the movie and is onscreen just long enough to walk around and be debriefed by everybody about Bane and the bomb, before he outlives his usefulness and the movie kills him off. That character exists solely as a receptacle for exposition. The film has other off-key moments, like when John Blake is speaking very calmly to Deputy Commissioner Foley (Matthew Modine), addressing him as “sir,” and Foley turns around and yells, “Someone get this hothead out of here!” The dialogue there seems incongruous with the emotion of the scene, in which Blake seems entirely level-headed, not hot-headed.

But I digress. What’s more relevant is that The Dark Knight Rises seems to flirt with major societal issues, only to skirt those same issues or leave them as mere overtones in a narrative that’s otherwise occupied with acting out the line, “This bomb is a time bomb.” Maybe I’ve likewise skirted any real point here, but I promise you, we’ve almost arrived at the bottom line.

People have wondered (or been preoccupied, if you will, with the nagging thought): what is Nolan trying to say with the Occupy Wall Street stuff in The Dark Knight Rises? Was it just a happy accident that he had Selina Kyle play the voice of the 99%, telling billionaire Bruce Wayne, “You’re all going to wonder how you could ever live so large, and leave so little for the rest of us?”

Gotham’s Last Hope

Here's what Christopher Nolan had to say about the temptation to read political meaning into The Dark Knight trilogy (via Uproxx):

“To be perfectly honest, we really try to resist at the script stage being drawn into specific themes, specific messages. Really these films are about entertainment, really they are about story and character. But what we do is we try and be very sincere in the things that frighten us or motivate us or [we] would worry about when you’re looking at ‘ok, what’s the threat to the civilization that we take for granted,’ and we grope at how we’re going to frighten ourselves essentially with a force of evil coming into a place. We try to be very sincere about that. And I think resonances that people find or that happen to occur with what’s going on in the real world, to me they come about really as a result of us just living in the same world that we all do and trying to construct scenarios that move us or terrify us in the case of a villain like Bane and what he might do to the world.”

It's been over a decade since The Dark Knight trilogy ended, but it feels increasingly like the trilogy synthesized trends and patterns in such a way that it foresaw some of what might happen in America and the world at large. My fear is that the U.S. is a powder keg, its own sort of bomb, waiting to go off in the next recession or presidential election. Batman manages to stave off Gotham City’s destruction, or self-destruction, for three movies, but history is written in blood, and it doesn’t always allow for the same happy ending as an aspirational superhero film, where the hero escapes certain nuclear death and lives to dine another day.

It's not my intent to fearmonger with this; I’m just expressing genuine concerns, some of which the movies seem to share. As we’ve hopefully established by now, The Dark Knight trilogy hit the zeitgeist and is full of synchronicities, another minor example being when Harvey Dent repeatedly refers to the Major Crimes Unit as the “MCU.” At the time, Iron Man was only two months old and the term “Marvel Cinematic Universe” wasn’t in usage yet.

Given that the concept originated from Carl Jung, and Batman’s villains are known for “conforming to Jungian archetypes,” it’s not such a stretch to say that an abundance of synchronicities manifests within The Dark Knight trilogy.

Now, with actors joining writers on strike for better working conditions, Hollywood has almost completely shut down, with Nolan’s blockbuster forefathers, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, having predicted years ago that the entertainment business was headed for an implosion. It’s my sincere hope that it can forestall that implosion and secure a better future for the people that make up the industry. The same goes for the American dream, which is nothing if not a beacon in the long dark night.